Assureur la sécurité de la ville d’Anvers avec RADWIN JET

Assureur la sécurité de la ville d’Anvers avec RADWIN JET

Published on August 26, 2020 | 0 views

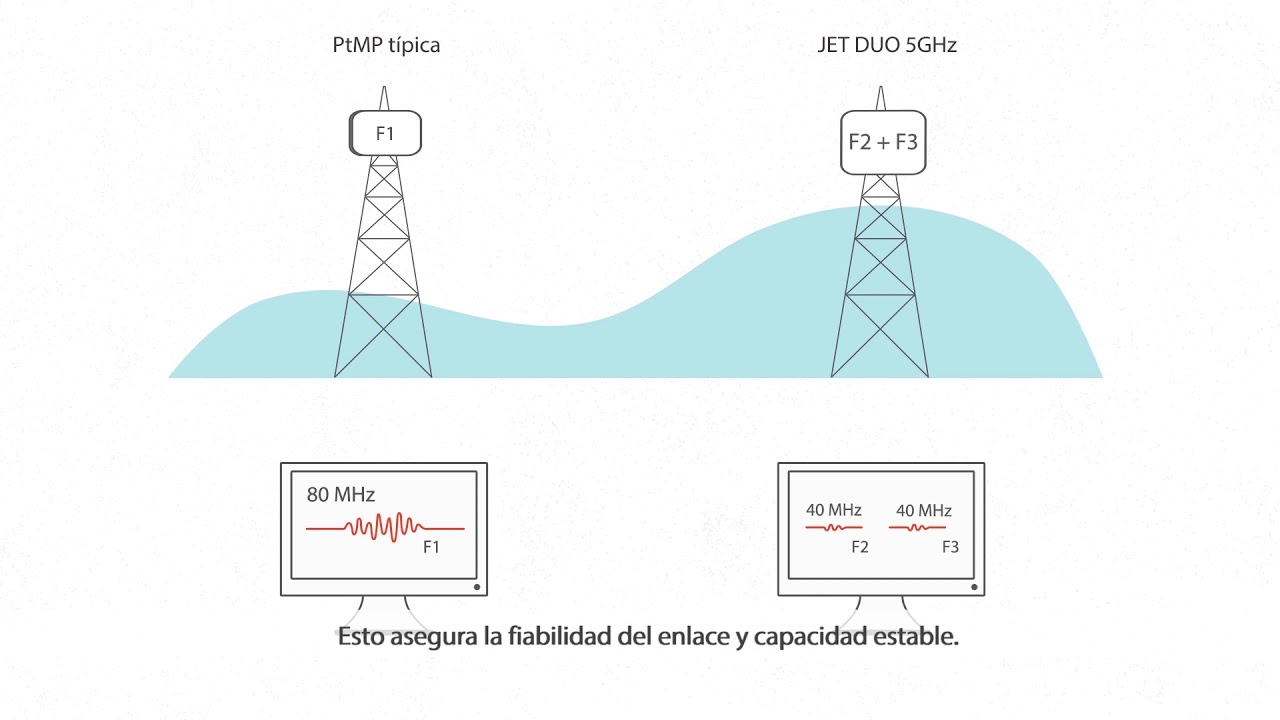

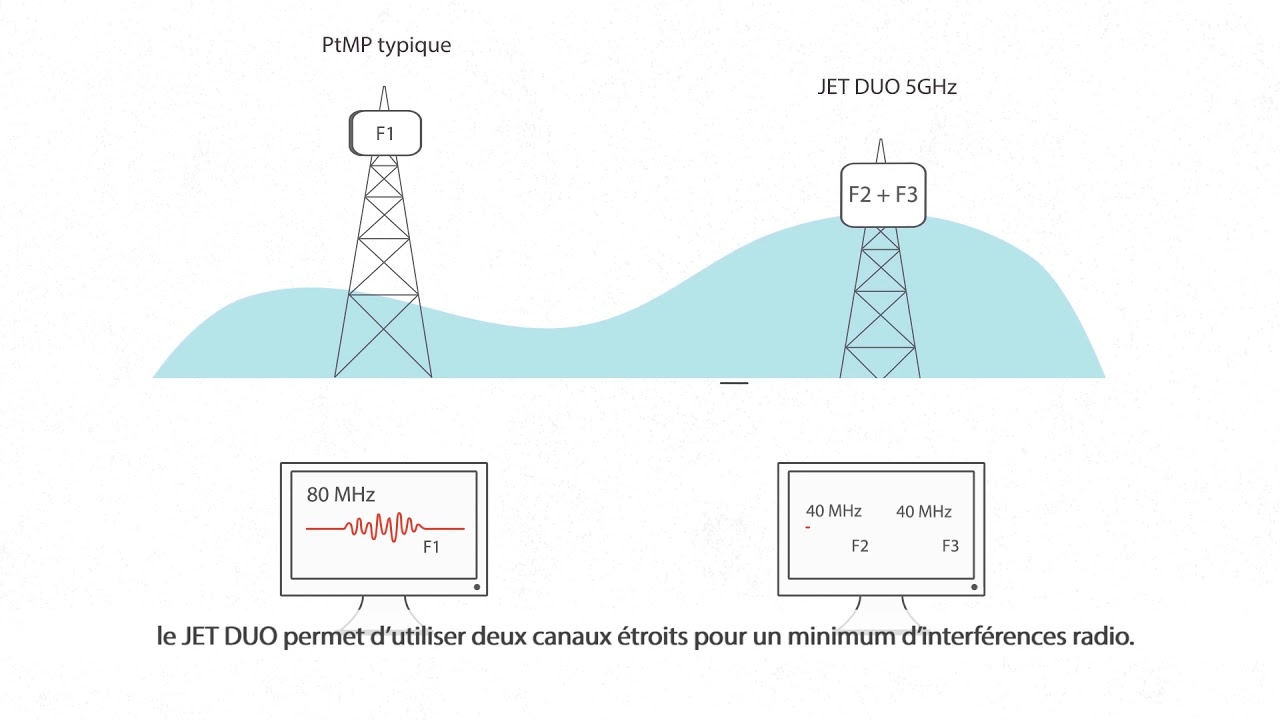

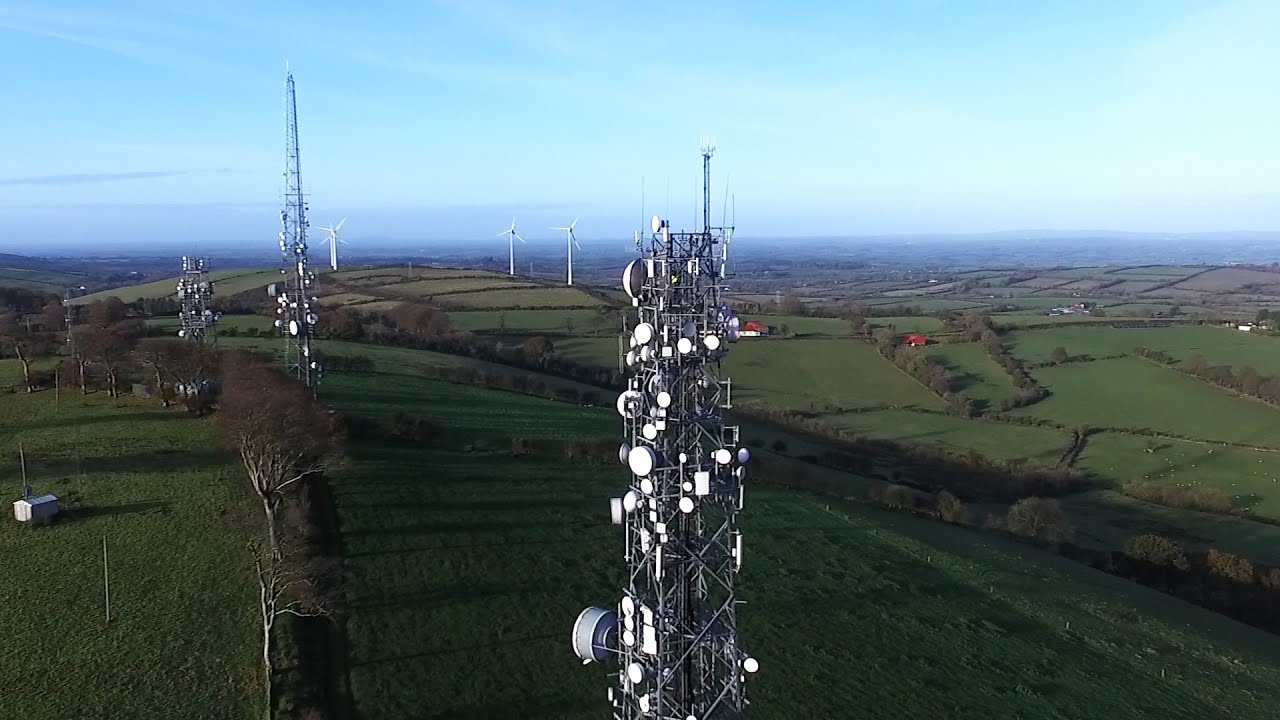

La police belge à Anvers a déployé RADWIN JET PtMP dans toute la ville pour diverses applications Smart City telles que la vidéosurveillance, la reconnaissance de plaques d'immatriculation, etc.

Back

Back